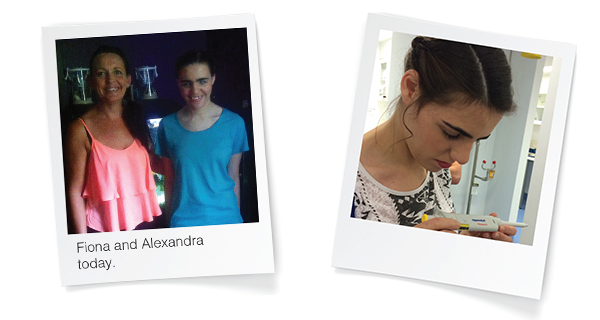

Alexandra, was born with congenital glaucoma and is being treated by glaucoma specialist, Dr Mark Chiang, at the Queensland Eye Institute.

Congenital glaucoma is a rare condition caused by the incorrect development of the eye’s drainage system during pregnancy. It leads to increased intraocular pressure and results in damage to the optic nerve.

Alexandra’s mother, Fiona, explained that there were no complications or tell tale signs that something might be wrong before she was born and her pregnancy progressed normally. When she was born, Alexandra didn’t open her eyes but, as she wasn’t breathing either, the main concern at the time was the lack of oxygen. Fiona recalls it like it was yesterday.

“I was very stressed and panicked because I didn’t know what was going on. Her eyes looked big like large marbles. ”

“I remember that there was a team of people looking at her and one of the nurses told me not to panic and that her eyes were just swollen because of the complicated labour.”

As the days passed, specialists could not pinpoint the cause of Alexandra’s eye condition and her parents grew increasingly worried. As soon as she was able to open her eyes a few days later, it became evident that there was something seriously wrong with her sight.

“They were all blue, totally blue.”

When Fiona was eventually discharged from the hospital, she noticed, within a week of bringing little Alexandra home, that her eyes started to go red and they looked as if they were getting bigger.

Trusting her maternal instincts, Fiona immediately got in touch with a Brisbane ophthalmologist for a second opinion. He diagnosed the condition as congenital glaucoma and instantly put her in touch with paediatric ophthalmologist Professor Glen Gole.

“He told me there was a real concern Ally was going to lose her sight. The pressures in her eyes were extreme at 55 and 35. I was told at the time; if it had been any longer her eyes would have perforated.”

Within five days, Alexandra was undergoing emergency surgery on her eyes at just two weeks old. After more than 60 examinations under anaesthetic in her first year Alexandra’s pressures continued to fluctuate.

Thankfully, today Alexandra’s glaucoma is now stabilised. However her treatment will be ongoing for the rest of her life to ensure any remaining vision is not lost.

She was also diagnosed with Aniridia, which is the absence of the iris and lost the vision in her left eye after a complete retinal detachment.

Alexandra’s remaining vision is in her right eye, which has regrettably developed a cataract and is not eligible for a corneal transplant due to the high risk of failure.

It remains a very complex situation to manage as one condition and treatment option may impact the other. However, Dr Chiang at the Queensland Eye Institute and our medical researchers are working hard to see if they can ensure Alexandra preserves as much vision as possible for her entire life.

Despite these complex conditions and setbacks, Alexandra can see colours and shapes as if she is looking through a frosted glass window. It is now up to Dr Chiang and our scientists to ensure this is not lost.

For Fiona it can sometimes become overwhelming as she lives everyday with the possibility that her daughter may go completely blind.

“She is only 19, how is she going to be ten years from now? I know we are never going to bring back her lost vision but we surely can ensure that the sight she currently has is preserved.”

Associate Professor Damien Harkin has been working in the field of stem cell research for 20 years and believes that we are on the right path to developing a therapy which could one day help patients like Alexandra.

“In Alexandra’s case, a donor transplant has a high risk of failure due in part to her immune system rejecting the donor tissue,” Associate Professor Harkin said.

“Our goal is to use stromal stem cells to suppress the local tissue immune response so that the donor tissue is not as easily rejected and so will have a greater chance of surviving and supporting patient vision for longer.”

Stromal stem cells were originally isolated from bone marrow and have since been found in numerous other tissues including fat tissues. The novelty of our stromal stem cells is that they have been isolated from the periphery of donated human corneas.

Stromal stem cells from other tissues typically display a range of useful immunological properties and so far this seems also true for corneal stromal stem cells.

“Given Alexandra’s age and the success of our stromal stem cell research, it’s not out of the question that she could one day successfully receive a donor corneal transplant to preserve the eye-sight that remains.”

Low risk patients should also benefit from this technology by retaining their transplants for longer, not just high-risk patients like Alexandra.

“We have the potential to do these things but a lot of it comes down to funding.”

Alexandra and her family are very excited by what is underway and are urging everyone they know to get behind Dr Harkin’s research.