Instinctively, people don’t enjoy having their eyes poked and prodded. They certainly avoid having foreign bodies placed under their eyelids. So it’s not surprising that for many people, wearing contact lenses can be uncomfortable, even distressing.

Sarah Oakleigh’s journey with impaired vision is typical of many young people and includes an episode with painful contact lenses.

The 38-year-old social worker was diagnosed with keratoconus in primary school, when she struggled to read the blackboard.

Keratoconus is a degenerative condition where the cornea – the clear, dome-shaped tissue covering the front of the eye – gradually thins and bulges outward into a cone shape. The changing shape can cause distorted and blurred vision, leading to significant visual impairment over time.

Vision changes can be managed with spectacles initially, but as the distortion and irregularity progress, glasses become less effective.

Through her teenage years and as a young adult, Sarah stopped wearing glasses and having her eyes checked. As she became responsible for her own health care, she decided to “just wing it”.

She only returned to the optometrist in her mid-20’s when a colleague commented on her constant squinting. For the next five years Sarah was busy, starting a family and living in Germany, managing her sight with vision-correcting glasses. Finally, back in Australia, Sarah’s condition reached the stage where glasses couldn’t help, and she turned to rigid contact lenses.

“I found them really painful,” Sarah says. “They caused me a lot of anxiety. So I didn’t go back to the optometrist for probably another four or five years, using glasses that weren’t good for me.”

Sarah knew she had to do something but her experience with rigid contact lenses proved a mental barrier.

“I got help from a psychologist to get me back to the optometrist,” Sarah says, “because I needed my eyes to be better”.

Sarah’s journey with keratoconus highlights the limitations of spectacles and rigid contact lenses for managing keratoconus. Fortunately, a new surgical treatment offers new hope to people like Sarah living with deteriorating vision.

CAIRS – a new treatment for keratoconus

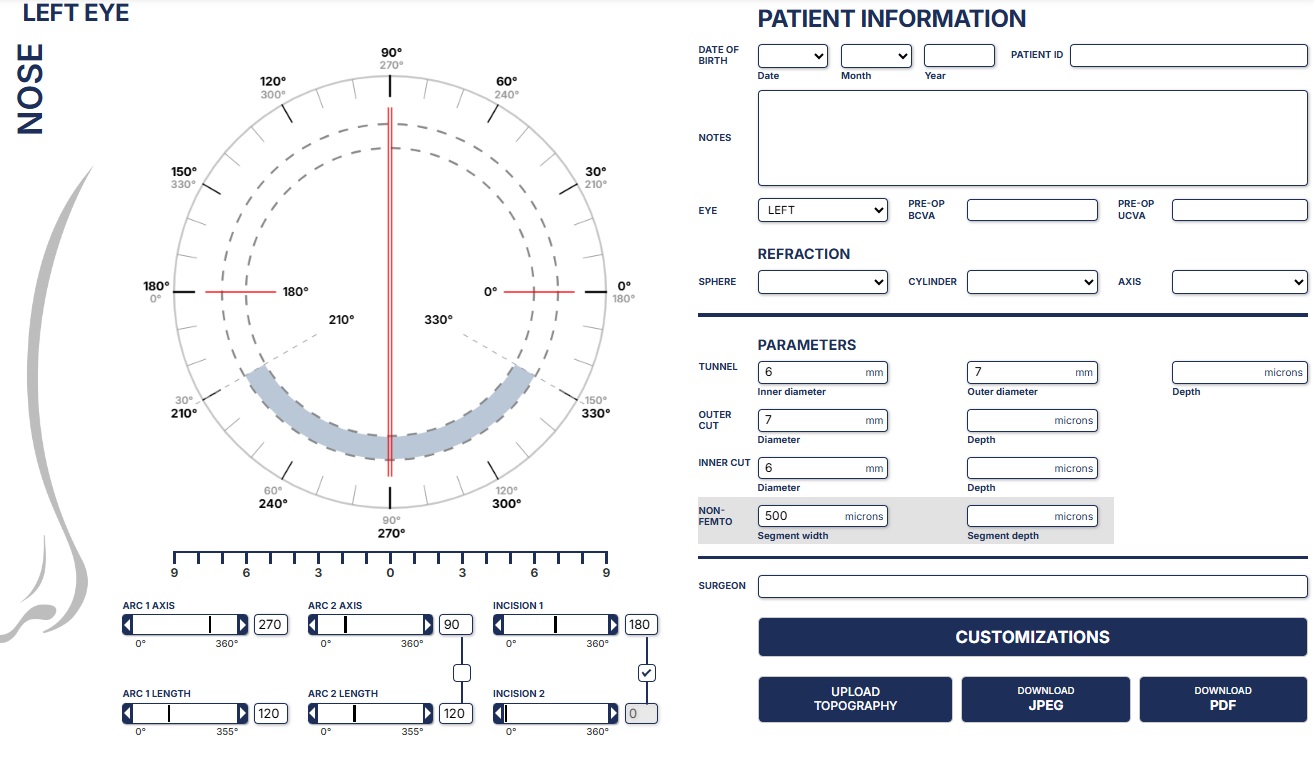

Corneal Allogenic Intrastromal Ring Segment (CAIRS) surgery uses donor tissue to create a scaffolding to reshape the cornea. The surgery reshapes the cornea by adding tissue to its outer edges. Channels are formed in the patient’s cornea with a laser, then donor tissue is cut to precise, customised dimensions based on the shape of the patient’s cornea and stitched into place.

Since CAIRS was developed nearly 10 years ago, scientific journals have reported significant improvement in uncorrected and best-corrected visual acuities, topographic parameters, and quality of vision for patients.

In Australia, CAIRS was pioneered by QEI ophthalmologists David Gunn and Brendan Cronin. Dr Cronin says CAIRS is a huge advance in the treatment of the disease. “I am so proud that the Queensland Eye Institute was the first Australian facility to offer this procedure to people suffering from poor vision due to keratoconus,” he says.

QEI research and education supporting CAIRS

Drs Gunn and Cronin continue to lead the field in advancing treatment for keratoconus and ectasia through their research and teaching related to CAIRS, supporting more clinicians to perform the surgery. In 2023 they launched a dedicated website for CAIRS, including a tool for ophthalmologists to plan surgeries.

Both doctors regularly host visiting specialists in their theatres to give instruction. They also publish and present their findings at scientific meetings in Australia and overseas.

Who is CAIRS for?

Dr Cronin says Keratoconus patients with moderate to severe disease who are not good candidates for other treatments, or have experienced insufficient results with those treatments, could benefit from CAIRS.

For patients like Sarah, who are unable to wear rigid gas permeable (RGP) lenses or scleral lenses due to discomfort, CAIRS can help improve vision and reduce the need for lenses.

Each patient should be carefully evaluated by a corneal specialist to determine whether CAIRS is the right treatment based on the severity of their condition, corneal thickness, and overall eye health.