Vision valued by a man of art and letters

Ray’s apartment in Kedron on Brisbane’s north is overflowing with books and artworks, with texts piled up on tables and chairs and frames resting on the floor, patiently waiting for vacant wall space.

Six years ago, Ray took up Japanese calligraphy (Shodo) and ink painting (Sumi-E) through the Brisbane Institute of Art, learning the discipline of restraint in colour and form required by these ancient pursuits.

Each piece can take weeks to create, the 81-year-old says, who works on his art a few hours each day.

“I do two hours at a time, and I’m exhausted at the end of it,” Ray says. “Because it’s concentrated effort.”

He learns from a Japanese teacher, in a class with mostly Japanese students, using imported brushes and ink, and paper that can cost up to $600 per sheet.

“I love the movement of it,” Ray says, moving his arms gently back and forth like he’s practising Tai Chi.

“It’s a challenge, which I like,” Ray says. “If I didn’t, I’d be out very quickly.”

Ray has reached the fourth rank in Shodo, which uses a similar grading system to karate, and his work is sent to Japan for exhibition and grading by a master.

“I don’t think I’ve ever got more than five out of ten,” Ray says. “He’s a tough hombre.”

Still learning after a lifetime of teaching

Ray’s pursuit of excellence and learning, even in retirement, comes as no surprise.

As a young man he taught in primary school but quickly moved into the Education Department to work on the curriculum. From there he moved to senior classrooms, teaching at high schools around southeast Queensland, before teaching education at the tertiary level.

“I was lucky because I was doing university work all the way through, so I was able to get promoted fairly quickly,” Ray says.

He later completed a Master of Social Science, followed by a Doctorate in anthropology, eventually earning an associate professorship at the Griffith Business School in the Department of Tourism, Hotel, and Sport Management, where he lectured in leisure studies and, later, managing culturally diverse workplaces.

“We had the biggest leisure studies school in the world at the time,” Ray says.

“We did a lot of travel overseas to conferences because people wanted to know about what we were doing.”

Travel has always featured in Ray’s calendar. As an academic he taught at universities in Australia and overseas, including Sydney, Hong Kong, Sweden and Canada. But a life devoted to reading, travel and art was turned upside down last year when a routine test by Ray’s optometrist revealed the tell-tale spots of macular degeneration.

Living with age-related macular degeneration

Ray’s optometrist referred him to the QEI clinic for monitoring and eventually he had surgery on his right eye to remove a cataract.

Then, despite ongoing monitoring, Ray’s macular degeneration led to a major bleed, causing him to lose sight in his left eye.

Prior to the bleed Ray had noticed some changes to his vision but didn’t realise how serious it was.

“I thought it would just go away,” he says. “I thought it was probably dust or something.”

QEI ophthalmologist Associate Professor Anthony Kwan says sudden deterioration like this is typical for those living with this disease.

“It’s important for patients who have risks of age-related macular degeneration to report any change in their vision immediately,” Dr Kwan says.

These symptoms include sudden blurring of central vision, distortion in vision, and a non-moving dark spot or spots that can appear in the central vision.

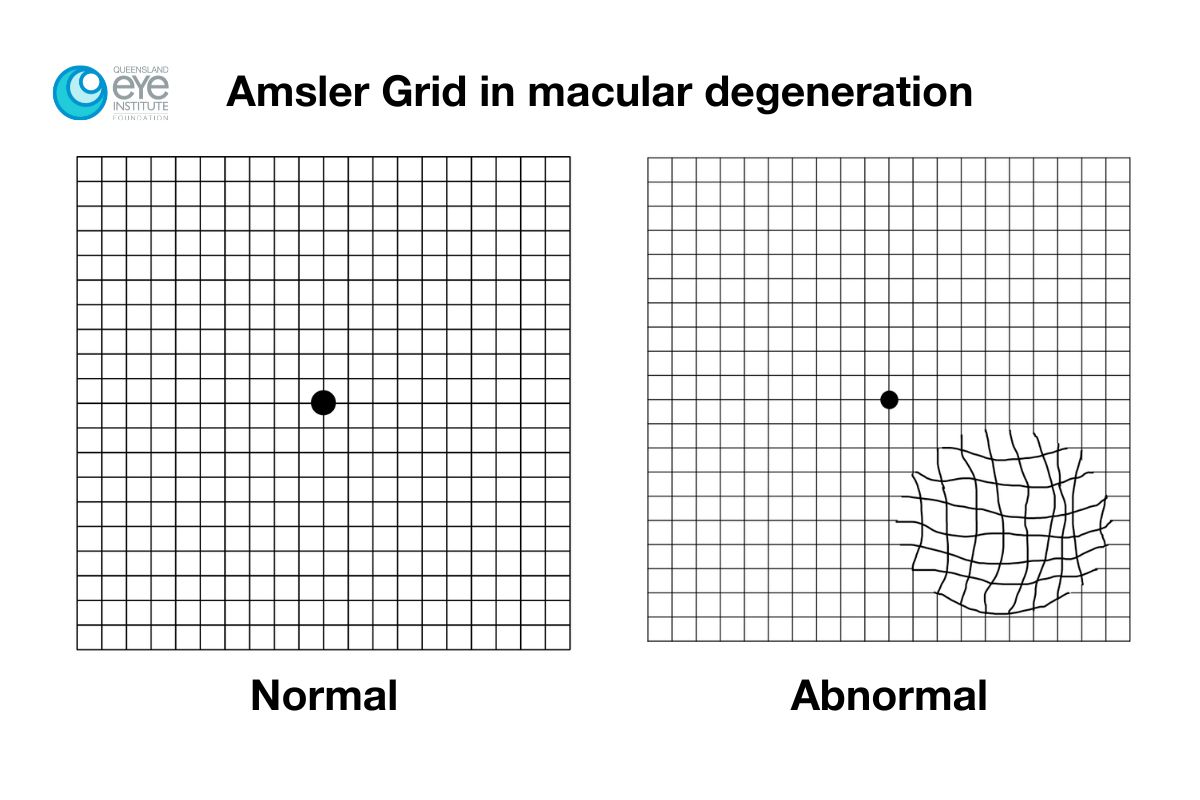

“Some patients use an Amsler Grid to monitor their vision,” Dr Kwan says.

“It’s not the most accurate test, but it serves as a guide.

“If in doubt, patients should seek help from their eye care professionals who can use modern, high-definition optical coherence tomography (OCT) scans to detect any signs of wet macular degeneration.”

Family legacy

Since learning the disease can be inherited, Ray has encouraged his three daughters to also have regular checks. His mother and aunt both had macular degeneration and lost their sight completely.

Ray watched his mother deteriorate in her early 70s, becoming restricted in her movements and struggling to do everyday tasks like boiling water. Eventually Ray and his sister made the difficult decision to put their parents into care.

“Her inability to do the things that she would normally do was affecting both her and my dad,” Ray says.

“It was tough for both of us to make that decision. But we thought if we don’t do this, it’s going to be worse because they’ll be dangerous to each other,” he says.

Adjusting to life with macular degeneration

Since suffering the bleed in his left eye Ray’s driving has been restricted. He won’t drive in the rain or at night when the headlights of oncoming cars bother him.

“I would absolutely hate anything to happen to my right eye because I would be pretty much lacking vision,” Ray says.

“I can see all of you now, with the right eye, that’s fine,” Ray says. “No problem at all.”

“But if I had two eyes like this,” he says, covering his good eye, “I’d be in trouble.”

“It was only when I started going to QEI that I learned about the genetic aspect of macular degeneration,” Ray says.

“My daughters are now getting tested regularly,” he says.

About Queensland Eye Institute

The Queensland Eye Institute (QEI) is Queensland’s oldest and largest independent eye health research institute, committed to long term research to develop effective treatments and cures. Our research team is actively involved in research for treatment of both dry and wet age-related macular degeneration, regularly participating in multi-centre trials testing new medications and treatments.

Learn more about age related macular degeneration on the QEI website here.